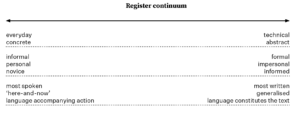

As teachers, our role is to move students from spoken to written realms and from written to spoken. We call this moving across the register continuum.

- At one end of the continuum (left), there is the most spoken language which usually happens face-to-face and accompanies some kind of action.

- In the middle of the continuum, spoken and written language overlap, so some texts are spoken-like but written and could be read aloud (eg. an email or narrative) or written-like but spoken (eg. an oral presentation).

- The other end of the continuum (right) is the most written end, where language is most reflective, where the text is constructed by the writer for an unknown reader, and deals with generalisations and abstractions.

Nominalisation is a major resource for moving across the register continuum. It can be defined as a linguistic process in which meanings that are typically realised by verbs, adjectives and conjunctions are realised more abstractly by nouns. It is used to realise more abstract meanings seen in written language and for building up technical meanings in the various subject areas.

Here are a few examples of nominalisations:

| She explained to her father why she failed but he didn’t accept it. | Her explanation for her failure was not accepted by her father |

| Carl was persistent and it paid off in the end. | Carl’s persistence paid off in the end. |

| He was confused and everyone knew it. | His confusion was apparent to all. |

| Many people in the area are not working because many of the small firms have recently closed. | High unemployment in the area has been caused by the recent closure of many small firms. |

| The crops failed because it didn’t rain all winter. | The reason for the crop failure was the lack of winter rain. |

Here, we can see that the verbs, adjectives and conjunctions in the more spoken versions (left column) have become nouns in the more written versions (right column). We can see these new forms as more metaphorical because we are breaking the usual link between processes being realised through the verbal group (‘explained’, ‘failed’) and attribute participants being realised through adjectives (‘persistent’). Instead, they are realised by nouns. We can see the effect this has on the clause. Where the meaning was initially realised through one or more clauses (‘she explained to him why she failed’), it is now realised by a nominal group (‘Her explanation for her failure’).

Also note how, with some nominalisations, the connection between the nominalisation and the verb or adjective is more direct (‘explained’ to ‘explanation’, ‘persistent’ to ‘persistence’) and with others less direct (‘are not working’ to ‘out of work’ to ‘unemployed’ to ‘unemployment’) and others even more cryptic (‘didn’t’ to ‘lack’). This is why nominalisation is often very difficult for students to develop control of.

Typically, teachers de-nominalise highly written texts that students encounter in the classroom but we need to ensure that students are taken back to the written end once they have understood the meanings at the more spoken, common-sense end. A shared understanding of the role of nominalisation by both the teacher and the students will make these shifts transparent and more likely to be taken up by the students.

You can download this article as a reading here.