This month, we give you practical tips on how to identify the differences between spoken and written language.

The nature of spoken texts is to construe the world as dynamic, focusing on processes that express human and non-human actions. To do this, spoken language relies on verbs to carry meaning.

In contrast, the nature of written texts is to construe the world as static, focusing on the participants in the processes and giving us time to describe, evaluate, reflect on and organise that dynamic spoken world. To do this, written language relies on nouns.

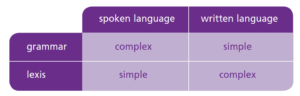

Importantly, it would not be accurate to say that written texts are more complex than spoken texts. Each kind of text, spoken and written, can be considered complex in its own way. Spoken texts have a grammatical complexity (or intricacy), while written texts have a lexical complexity.

By grammatical complexity, we mean that the clauses are joined together in myriad logical ways: some are combined with linking conjunctions of addition, others by binding conjunctions of cause or time, others by projection, for example.

By lexical complexity, we mean that the nominal groups are expanded greatly, often to the extent that there is a high degree of embedding in the qualifier.

How to identify the differences between spoken and written language?

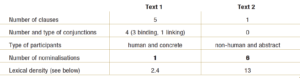

Activity: identify the differences between Text 1 and Text 2 by completing the table below.

Text 1

Class 8B still visited the museum / even though the Egyptian exhibition had been delayed / because the curator had been taken ill / and the west wing had been closed off / because they were renovating.

*/ is used to separate each clause. What is a clause? It is the basic building block of language, which is grouped around some kind of process (expressed by a verbal group). Sentences can be made up of one clause alone or a combination of more than one clause.

Text 2

Class 8B’s visit to the museum was not stopped by the delay of the Egyptian exhibition because of the curator’s illness nor the closure of the west wing due to renovations.

How to calculate lexical density?

To calculate lexical density, we need to be able to distinguish lexical items from grammatical items.

Lexical items belong to an open set in the sense that we can get new lexical items frequently and constantly added to a language. Lexical items include most nouns, verbs and adjectives, and many adverbs.

Grammatical items, however, make up more of a closed set in the sense that we very seldom add new grammatical items to the language. Think back to the last time you can remember when a new grammatical item was added: a new conjunction or a new article for example. Maybe hundreds of years have passed! Grammatical items include determiners, conjunctions, prepositions, finites, relational processes, pronouns and many adverbs.

Note that embedded clauses are not included in the total number of clauses for calculating lexical density.

Once you have identified the total number of lexical items and the total number of clauses, the lexical density can be calculated by dividing the total number of lexical items by the total number of clauses. When calculating lexical density, it is best to use a substantial section of a text so that the average is more accurate. A complete text with lexical density of 13 would be extremely difficult to read.

Spoken texts generally have very low lexical density and 3 would not be unusual at all, while written texts are generally around twice that number, 5 or 6. The lexical density of a student’s written text can act as a warning signal. If secondary school students are consistently writing texts (not narratives or personal recounts) with a lexical density of around 3, then this would be a problem because we expect these students to be writing texts with a lexical density of around 6 or so.

Solution