This case study describes the work of Loredana Saracini-Palombo, a Year 6/7 teacher at St Mark’s Lutheran Primary School in South Australia. In 2009, Loredana also took on a role of mentoring other teachers in the school in explicit, contextualised teaching of literacy. St Mark’s Lutheran pedagogy is underpinned by a teaching and learning cycle.

Although this research was well documented at the time, it was never widely disseminated. We are making it available here because it remains an excellent example of the gains to be made when a shared functional metalanguage is a key part of any literacy pedagogy.

By Loredana Saracini-Palombo and Bronwyn Custance

Early in the school year, through the vehicle of a focus Genre (usually Narrative because it draws on a wide range of clausal relationships), Loredana and her class revisit and work through the notion of what a clause is, its constituents and the various ways clauses can be combined. She does this because she believes it is a fundamental part of understanding written texts. She is aware of the need for students to have control over a range of linguistic resources for combining clauses in order to make the range of complex meanings demanded by the middle years curriculum. Therefore, she wants to ensure that her students have these understandings and resources and the accompanying metalanguage, which will allow her to readily refer back to these understandings and resources at every part of the teaching and learning cycle as she and the students work on this and other focus genres throughout the year.

Loredana has shared her explicit Genre-based approach to teaching functional grammar and its metalanguage with a colleague, Matthew Vince, who teaches the other Year 6/7 class. After Loredana’s initial support, such as occasionally combining the two classes so that she could model the teaching of a particular aspect of language, Matthew now employs much the same approach.

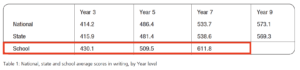

Their approach is reaping rewards as there is a marked difference in their Year 7 national literacy test results, with their students strongly outperforming state and national averages. While the school’s literacy results are above state and national averages in Years 3 and 5, the Year 7 results have further increased the lead and significantly outperform Year 9 state and national averages.

This is true in every aspect of the literacy tests. However, only figures for writing are included here in Table 1.

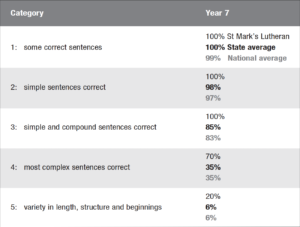

When one looks at the breakdown of student performance across the writing criteria, the difference in student achievement at the more complex higher levels in the rubric is stunning. A comparison of the school results for ‘Writing criteria: Sentence structure’ against state and national averages is included in Table 2.

Even more important than the strong performance in the NAPLAN tests, however, is the change in the students’ perception and confidence in themselves as writers, and in the teachers’ sense of making a difference for their students. Matthew continues to be impressed by the work his students now produce and felt a deep sense of satisfaction when several boys remarked to him that they had never thought they could write like that.

How did they achieve such a result?

What we can see through Loredana’s work is that explicit teaching allows teachers and students to generate a language to talk about language, a metalanguage. This not only helps in teaching but also benefits assessment processes. In assessment of learning, there is no longer a need to tell students that their piece of writing was ‘good’ or ‘excellent’. We can be far more explicit, referring to the use of processes, sentence complexity, lexical choices and so on. We are also able to use assessment as learning with students, who are able to identify areas for improvement, because they have been provided with the necessary tools to do so.

Read the full case study on how Loredana implemented the explicit teaching of sentence structure.